Dec. 31, 2022

Happy Accidents of the Artificial Unconscious

This is the text of a presentation given in August 2022 at VSAC research conference, in a symposium named "Unexpected realities: how uncertainty and imperfection influence perception and interpretation in digital visual studies" organized by Darío Negueruela del Castillo, Eva Cetinić and Valentine Bernasconi.

Artificial Intelligence may bring something entirely new: it may “simply” be a tool, but it is a tool with a strong personality, that we need to engage a dialogue with.

Navigating the Infosphere

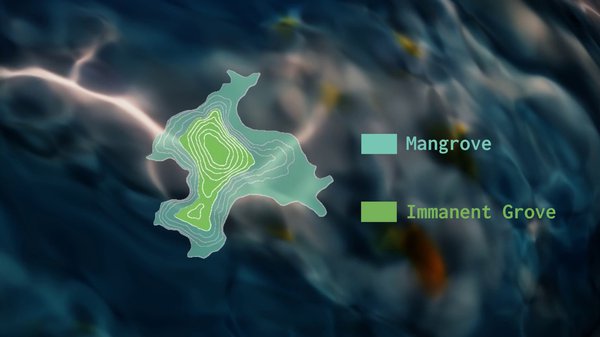

Now, I would advise you to take a raincoat and a life jacket, I’m embarking you for a trip on a very special ocean: the one of information exchange and production. We could follow the philosopher Kenneth E. Boulding’s framing and call this ocean Infosphere. This ocean, Infosphere, is made of all the information fluxes, communication, data, of our lives: not only the digital ones – from our phones and computers, – but mostly the “natural” stimuli – sounds, visual perception, speeches, smells…

Our minds are part, and agents, of this Infosphere. They are like little islands, experimented navigators floating on this vast ocean, processing all the stimuli flowing from the outside, creating abstract ideas and communicating them with others.

How does the reasoning take place? Thanks to a forest growing on the whole island. Close to the shore, there is a large mangrove, filtering all the water flowing in, and protecting the solid ground from the storms. This is our Cognitive Unconscious (according to the neuroscientist Lionel Naccache), or "System 1" (for the psychologist Daniel Kahneman). That mangrove processes in parallel the output or our senses, and chooses in all the stimuli perceived what deserves to reach the innermost layers: the face of a friend, or the alarm beeping in the morning.

On the ground, a much denser part grows: an Immanent Grove. It is where the most advanced reasoning takes place: the “System 2,” conscious, reflective thinking, allowing us to do high-level actions, like planning our day, making big decisions, or finding what to say in an academic conference – but in a sequential, less efficient way.

Water flows both ways, on the mindful island: the mangrove does not only filter the content coming in, it also acts, performs. It keeps our balance when walking, it articulates words with our mouths, it catches the objects that we’re thrown.

But it’s not even that hierarchical: this whole forest, grove and mangrove, is a large rhizome. For instance, memories are little crabs, fish, animals, hiding below the roots of every tree: System 2 needs System 1 to recall them, and remember. Even what seems “advanced” is actually done by the mangrove: putting an abstract idea into words; recognizing symbols, letters; imagining objects, visualizing places… The limit between the mangrove and the ground is never clear, varying with the tides.

Rising waters of cyberspace seas

Though they have been navigating the Infosphere for a long time, our minds are now faced with a very new sea: Cyberspace. Its streams are made of vast amounts of data packets, translated into 0s and 1s. We need special devices to access those fluxes: smartphones, computers, watches, connected fridges.

Cyberspace’s waters have been constantly rising since its very opening, in late 80s. And on that sea, new floating objects have recently appeared: Artificial Intelligences. They’re concretions of the massive amounts of data exchanged – and stored – there, resulting in Unidentified Floating Objects. Are they islands like our minds? Not quite. But they already do a pretty good job imitating what our mangrove does: recognizing faces; imagining objects, situations; generating sentences in an automatic way, word after word, like in surrealist automatic writing. AIs are sure part of this watery world – haven’t you noticed how “liquid” are GAN images? As impressive as GPT3 may be, it only answers articulating fragments from the immense quantity of text it read in an approximative way, fabulating credible but not so imaginative stories or conducting often inattentive reasonings, that may be plain wrong if it hasn't seen anything similar – all which our system 1 can very well do (after enough training).

Those rising waters might threaten to drown us, and carry us away, forever caught scrolling our social media app. The good news is that our mangrove is very good at one thing: predicting what’s coming next. Our brain is constantly optimizing our attention, to minimize the energy spent in system 2 – a cautious, but slow mode of thinking. This allows us to ignore much of what’s too common, too expected.

Companies have understood that, and they’re not trying too hard to catch our attention anymore: social media apps are made to be themselves liquid, fluid, with no hurdle, so they can maintain us in that hypnotic state where very little unexpected events happen; so they can taint our mangroves’ waters with the ads they’re selling.

I have noticed that, and yet, I am still looking regularly to social media. Why? Beyond those mechanisms, I think I’m rarely just interested in one particular image, but more in what specific artists do. I like the narratives they build, the message they convey, and how they evolve with time. I connect, relate – or not. There’s something beyond the technicality of what they make, and even beyond their creativity, that I appreciate. A diffuse pattern, a personality, a message. That AI mostly lacks, at least out-of-the-box.

In the end, it’s a matter of expression more than creation. The machine has no desire, no opinion on the world: it’s the human that provides it.

Collaborating with the machine

The computer, indeed, remains a tool. And it leads me to my main argument: how to use it, to create (hopefully) meaningful artworks?

While scientists are mostly working on making algorithms good at imitating humans, artists are usually looking for tools helping them in more specific tasks, with which they can pursue and extend their own practice.

Such tools are becoming more and more common, and powerful. As they are new, there is little distance on them so far. Yet, some interesting analyses now appear, such as “The Great Fiction of AI” published in July in The Verge.

In that article, AI is described by a writer who uses it as “A crazy [collaborator], completely off the wall, [...] who throws out all sorts of suggestions, who never gets tired, who’s always there.” It made it much easier for her to write complex descriptions and create atmospheres. But then she realized that relying too much on it made her lose the track of the global outcome: she was so seduced by the machine’s suggestions, focused on “what’s next,” that she couldn’t see the big picture anymore.

This outlines a first rule for a fruitful collaboration with the AI: you need to know where you’re going, to set your expectations, in order to assemble a consistent and meaningful work.

But it’s not exactly what I want to do. I am not only using the machine as a helper to build my narratives: I want to question the machine itself. I need to examine what AI suggests for what it is. I want to understand how those artificial mangroves behave, and what they tell about ours.

In doing so, I have to remain open. Notice patterns that emerge, and how they connect with what I was looking for – or not. See beyond, what doors the machine opens, where it could lead to, how it differs from my prevision.

Harvesting happy accidents

Bob Ross, a famous American TV painter teacher, would say “there’s no mistake; only happy accidents.” I want to find the happy accidents of the machine. I want to be surprised, but not too much – when everything is an unexpected signal, it’s bare noise.

To face another Unconscious, one has to open their own. And I want the spectator to experience it too. It’s a thin path on the fringe of machine’s sanity, almost a trance, that has to cost me something. It requires all my attention, as I need to keep being assessing whether the proposition of the machine seems promising, or not so much. What’s surprising, what’s not.

I said earlier that AI lacked personality: it’s not that true. It actually has many, but they can emerge only when you let them be. Commercial projects such as OpenAI GPT3 or DALL-E are reluctant to let it be so: they put technical restrictions, containment measures, to prevent it from generating bad things – be it sexual images, depictions of violence, or nonsensical outputs. There’s no surprise without risking anything; there’s no happy accident without the possibility of disappointment.

So I find it easier to work with smaller networks that can run on my computer, without constraint on their outputs. But it comes at the cost of an uneven quality. Then, it’s the artist-curator that has to find the jewels in the middle of many options, to bring the coherence and meaning.

This way, you can push AI towards its limits. Explore its failures, what it doesn’t know, or understand. Provoke bugs, glitches, that uncover the inner processes, and strangely resemble our own hallucinations – enough to make us feel the uncanny, the uncomfortable.

In my work, more specifically, I’m making narratives in which I intertwine all those concerns. I try to explore my own fears and to sketch out possible futures, through the otherness of the machine, like in the artworks that you’ll be able to see on this website.

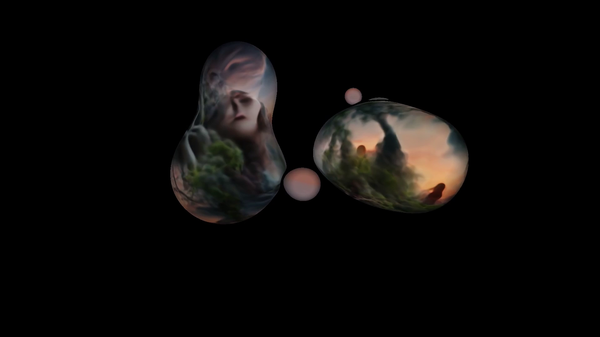

I don’t know if I’m really successful on that matter, but I want to use AI as a mirror to our irrationality. Make us plunge into that floating attention with images that evoke more than they show. Make the machine generate works that can’t be seen but in distant reading, like the weird animation that I’m showing as a presentation. Blurry, strange shapes, with ambiguous but meaningful patterns. Resonances are strong when things are undercover.

And that’s a long quest, under the shades of diverse forests, beautiful or uncanny, on stormy seas.